What we say, hear and sing in worship shapes our faith. In the case of words, rhythm and rhyme create poetry, clothing the words so they might penetrate deeper into the mind and soul, giving strength to the logos hidden behind the words. In the case of poems, melos (melody) blends with the logos so as to bring us more easily before the Lord, in turn, affecting our whole being through the direct, intimate one-on-one contact with God and persuading us to good works. In short, as St John Chrysostom would write in the fourth century, the poetry (logos) and melody (melos) make the process of prayer and the catechetical word less a chore.

“When God saw that many men were rather indolent, that they came unwillingly to Scriptural readings and did not endure the labor this involves, wishing to make the labor more grateful and to take away the sensation of it, He blended melody with prophecy in order that, delighted by the modulation of the chant, all might with great eagerness give forth sacred hymns to Him. For nothing so uplifts the mind, giving it wings and freeing it from the earth, releasing it from the chains of the body, affecting it with love of wisdom, and causing it to scorn all things pertaining to this life, as modulated melody and the divine chant composed of number” (PG LV, 155-159, from St John Chrysostom’s homily on Psalm XLI).

The strength of the metered word and modulated melody appear at both the most joyous and most difficult, even tragic, points of human existence. When the people of Israel crossed the Red Sea, “then sang Moses and the children of Israel this song unto the Lord, and spake, saying, I will sing unto the Lord, for he hath triumphed gloriously…” (Ex. 15. 1). On the other end of the spectrum of human existence, in the late 1940s, shortly before his death in a Siberian prison camp, a Russian Archpriest by the name of Gregory Petrov composed his own song to the Lord, an Akathist of Thanksgiving, in which, amidst all his personal suffering, his spirit welling up with gratitude, confessed:

“Immortal King of the ages,

Holding within your right hand

all the paths of human life

Through the power of your saving providence,

We thank you for all your acts of goodness,

Manifest and hidden, for the life on earth,

And the heavenly joys

of your kingdom to come.

Extend your mercy also into the future

for us who sing:

Refrain. Glory to you, O God, unto the ages.”

So it is clear that at the point of origin of any divine hymn or sacred musical composition is the relationship of prayer, a dialogue with God, either man reaching out to God or God touching man. The hymn or music is either the believer’s vocal response to contact with the divine or the believer’s attempt to reach out to the divine in thanksgiving, doxology or supplication. Apart from being a means of worship, it is also clear that the root of the rhythm (poetry) and sound (melody) of sacred music is also an inspired expression of faith. A confession of what one believes about God, the Saints, neighbor and the world he or she lives in. As such an expression it is worthy of examination. In time, over the centuries, changes in hymn forms will be related to changes in liturgical development and liturgical worship (practice), evolving especially during times of dynamic social change in the life of the Church, times where the theology (thought)—the perception of how one’s faith is to be lived—is challenged, be it from within or without. Theological and sociological developments interact, leaving some mark on liturgy, whether it be the hymns or their music. This form of looking at liturgical music from the vantage point of its place in the history of liturgy and an expression of social change is a widening of the fields of musicology and theology.

Thursday, December 30, 2004

Tuesday, December 28, 2004

Nativity Vigil

This year I celebrated the feast of our Lord's Nativity with a vigil at a women's monastery on Hymitos mountain, must be Koropi. The monastery's katholikon is dedicated to the Nativity and is known as "Bethlehem." We started at about 10:30PM and finished around 6:30AM. I was on the road back to Piraeus by 7AM and caught the 8AM boat back to Aegina.

There's always alot of talk about how "beautiful" Christmas is in the West (i.e. US, UK, Germany, etc.), but I think there's no match to the spiritual stregnth that should and could be.

In recent years, apparently influenced by powers not known to me, there is a push to begin services later and later. The idea is that people can't wake up early for Church. When I came to Greece for studies the first time, back in 1988, I remember entering a Church on Christmas morning at 5:15AM and not finding a seat! The announced time for the start of the service was 5AM. If you check the old "Farlekas," you see that ten, twenty and thirty years ago the services began even earlier—3:15AM, 4AM. We would call this a "Sunrise" service in American Protestant circles. It's basically an abbreviated vigil service for the parishes.

The monastic diataxis begins with the Great Apodeipnon up to the doxology and then finishes the vespers that was not completed in the morning by going directly into the Lity, Aposticha, Blessing of the loaves and then continues as would any other vigil, with the reading, hexapsalmos and the rest of the orthros followed by the hours, metalipsis, typika and divine Liturgy.

The parish diataxis (Konstantinos/Biolakes typika) begins with a kind of mesonyktikon, followed by the orthros and divine Liturgy.

In America most Orthodox Churches are mostly empty on Christmas morning. The parishes with more than one priest, with the blessings of the bishops, have moved the services to early afternoon. This means all the larger cathedrals. People wanna come to Church early in the evening, take communion and then go home, open presents and feast. Christmas morning becomes a sleep-in day.

How is this a "beautiful" Christmas?

Christmas is not lights, decorated trees, presents and richly laden tables…

"O Lord my God, I know that I am not worthy, nor sufficient, that Thou shouldest come under the roof of the house of my soul, for all is desolate and fallen, and Thou hast not in me a place worthy to lay Thy head. But even as from on high Thou didst humble Thyself for our sake, so now conform Thyself to my lowliness. And even as Thou didst deign to lie in a cave and in a manger of irrational beasts, so also deign to lie in the manger of mine irrational soul and to enter my defiled body."

This is the attitude the Church fathers brought to Christmas prayer.

Somehow, it seems to me that the situation in America is more than assimilation. Something else is operative. Something un-American. To what extent do allow a weak, Anglo-Protestant worship life to infiltrate into our rich Orthodox Christian heritage? God forbid anyone take the tyropittes, spanakopittes, pastitsia and feta cheese off our Christmas dinner menu. Then we'd get upset!

Have we maybe taken something much more worthy off our "table"?

There's always alot of talk about how "beautiful" Christmas is in the West (i.e. US, UK, Germany, etc.), but I think there's no match to the spiritual stregnth that should and could be.

In recent years, apparently influenced by powers not known to me, there is a push to begin services later and later. The idea is that people can't wake up early for Church. When I came to Greece for studies the first time, back in 1988, I remember entering a Church on Christmas morning at 5:15AM and not finding a seat! The announced time for the start of the service was 5AM. If you check the old "Farlekas," you see that ten, twenty and thirty years ago the services began even earlier—3:15AM, 4AM. We would call this a "Sunrise" service in American Protestant circles. It's basically an abbreviated vigil service for the parishes.

The monastic diataxis begins with the Great Apodeipnon up to the doxology and then finishes the vespers that was not completed in the morning by going directly into the Lity, Aposticha, Blessing of the loaves and then continues as would any other vigil, with the reading, hexapsalmos and the rest of the orthros followed by the hours, metalipsis, typika and divine Liturgy.

The parish diataxis (Konstantinos/Biolakes typika) begins with a kind of mesonyktikon, followed by the orthros and divine Liturgy.

In America most Orthodox Churches are mostly empty on Christmas morning. The parishes with more than one priest, with the blessings of the bishops, have moved the services to early afternoon. This means all the larger cathedrals. People wanna come to Church early in the evening, take communion and then go home, open presents and feast. Christmas morning becomes a sleep-in day.

How is this a "beautiful" Christmas?

Christmas is not lights, decorated trees, presents and richly laden tables…

"O Lord my God, I know that I am not worthy, nor sufficient, that Thou shouldest come under the roof of the house of my soul, for all is desolate and fallen, and Thou hast not in me a place worthy to lay Thy head. But even as from on high Thou didst humble Thyself for our sake, so now conform Thyself to my lowliness. And even as Thou didst deign to lie in a cave and in a manger of irrational beasts, so also deign to lie in the manger of mine irrational soul and to enter my defiled body."

This is the attitude the Church fathers brought to Christmas prayer.

Somehow, it seems to me that the situation in America is more than assimilation. Something else is operative. Something un-American. To what extent do allow a weak, Anglo-Protestant worship life to infiltrate into our rich Orthodox Christian heritage? God forbid anyone take the tyropittes, spanakopittes, pastitsia and feta cheese off our Christmas dinner menu. Then we'd get upset!

Have we maybe taken something much more worthy off our "table"?

Saturday, December 25, 2004

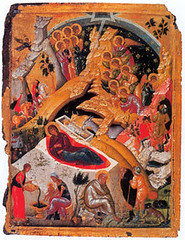

15th c Nativity icon; Athens: Byzantine Museum

Oikos.

Bethlehem opened Eden, come let us behold;

We have found joy in this hidden place,

comelet us seize

The pleasures of paradise within the cave;

There appeared an unwatered root

which sprouted forgiveness;

There was found an undug well

From which David once yearned to drink;

And there the Virgin brought forth an infant

Who at once quenched their thirst,

that of Adam and of David.

Come, then, let us hasten to this place

where there has been born

A newborn babwe, the pre-eternal God.

St Romasnos Melodos

Prayers for a blessed Christmas and New Year full of His grace!

Bethlehem opened Eden, come let us behold;

We have found joy in this hidden place,

comelet us seize

The pleasures of paradise within the cave;

There appeared an unwatered root

which sprouted forgiveness;

There was found an undug well

From which David once yearned to drink;

And there the Virgin brought forth an infant

Who at once quenched their thirst,

that of Adam and of David.

Come, then, let us hasten to this place

where there has been born

A newborn babwe, the pre-eternal God.

St Romasnos Melodos

Prayers for a blessed Christmas and New Year full of His grace!

Tuesday, December 21, 2004

Tradition and Change: American Assimilation vs Acculturation

It's really everywhere if you stop and think, even the Iraqi war. Age-old traditions with a history, cultural life and outlook all their own coming face to face with modernity in the post-modern world. When either side seems threatened, tradition or change, the meeting point can contain a degree of tension. It is a challenge to both sides.

Relating to the sacred sound, the traditional psaltic art of the Orthodox Christian Church, especially Hellenic in origin, but subsequently affecting the other linguistic Orthodox traditions, it is no secret that this age-old sacred chant form, more commonly known as Byzantine Chant, has been challenged in the context of North American Orthodox Christianity. And I think it's fair to say, not just the chant, but that would get us onto other topics.

The basic question is how to acculturate this aspect of Orthodox Christian practice without assimilation into modern, secularized American "entertainment" worship. There's much to explain and much to explore, but there is also much to be gained.

What was most surprising to me, when I was finally face to face with the reality, is the fact that the challenge was not unique to the American cultural scene. The sacred music problem in the North American Orthodox Christian jurisdictions coming out of this liturgical chant tradition is actually a carry-over from the old country. It's the same challenge modernity gave to sacred Orthodox Iconography, another age-old liturgical art form, and even monasticism. The difference is that while both traditional liturgical art forms—iconography and chant—eventually prevailed in Greece and other traditionally Orthodox homelands, the same has not occured in North America for the chant.

Amidst the backdrop of all the talk on Orthodox leadership, clergy-laity relations, autocephaly, archdiocesesan and parish by-laws, parish councils, uniform codes and the rest, the tiny corner of our traditional liturgical chant will, no doubt, be viewed as quite an esoteric exercise by many, maybe even most.

Relating to the sacred sound, the traditional psaltic art of the Orthodox Christian Church, especially Hellenic in origin, but subsequently affecting the other linguistic Orthodox traditions, it is no secret that this age-old sacred chant form, more commonly known as Byzantine Chant, has been challenged in the context of North American Orthodox Christianity. And I think it's fair to say, not just the chant, but that would get us onto other topics.

The basic question is how to acculturate this aspect of Orthodox Christian practice without assimilation into modern, secularized American "entertainment" worship. There's much to explain and much to explore, but there is also much to be gained.

What was most surprising to me, when I was finally face to face with the reality, is the fact that the challenge was not unique to the American cultural scene. The sacred music problem in the North American Orthodox Christian jurisdictions coming out of this liturgical chant tradition is actually a carry-over from the old country. It's the same challenge modernity gave to sacred Orthodox Iconography, another age-old liturgical art form, and even monasticism. The difference is that while both traditional liturgical art forms—iconography and chant—eventually prevailed in Greece and other traditionally Orthodox homelands, the same has not occured in North America for the chant.

Amidst the backdrop of all the talk on Orthodox leadership, clergy-laity relations, autocephaly, archdiocesesan and parish by-laws, parish councils, uniform codes and the rest, the tiny corner of our traditional liturgical chant will, no doubt, be viewed as quite an esoteric exercise by many, maybe even most.

Wednesday, November 10, 2004

Sleeping in

What time does Liturgy begin there in Greece? Why should we start early vs later?

Papouli,

The schedule of services throughout the year for the archdiocese of Athens are published in the dypticha each year; you can get an idea from there.

From St John Chrysostom's eighth baptismal catechesis:

16. I exhort you, therefore: let us seek the things which abide forever and never change. It was fitting, therefore, that I brought up this matter and that I exhorted all of you together, both those who have been initiated in the past and those who have just deserved the gift of baptism. On the days when we were continuously present at the tombs of the holy martyrs, we received an abundant blessing from those holy ones and enjoyed the rich benefit of their instruction. From now on, the continuity of our meetings will be broken off; hence, I must remind your loving assembly to keep ever ringing in your ears the memory of the important instruction those holy martyrs gave, and to hold spiritual things of greater importance than all the goods of this life.

17. And I urge you to show great zeal by gathering here in the church at dawn [orthron] to make your prayers and confessions to the God of all things, and to thank Him for the gifts He had already given. Beseech Him to deign to lend you from now on His powerful aid in guarding this treasure; strengthened with this aid, let each one leave the church to take up his daily tasks, one hastening to work with his hands, another hurrying to his military post, and still another to his post in the government. However, let each one approach his daily task with fear and anguish, and spend his working hours in the knowledge that at evening he should return here to the church, render an account to the Master of his whole day, and beg forgiveness for his falls. For even if we are on our guard ten thousand times a day, we cannot avoid making ourselves accountable for many and different faults. Either we say something at the wrong time, or we listen to idle talk, or we think indecent thoughts, or we fail to control our eyes, or we spend time in vain and idle things that have no connection with what we should be doing.

18. This is the reason why each evening we must beg pardon from the Master for all these faults. This is why we must flee to the loving-kindness of God and make our appeal to Him. Then we must spend the hours of the night soberly, and in this way meet the confessions of the dawn. If each of us manages his own life in this way, he will be able to cross the sea of this life without danger and to deserve the loving-kindness of the Master. And when the hour for gathering in church summons him, let him hold this gathering and all spiritual things in higher regard than anything else. In this way we shall manage the goods we have in our hands and keep them secure.

In the above we see St John's late fourth-century Constantinopolitan daily prayer programme for his flock. Notice, these are not monastics, but lay believers with all sorts of jobs. It is evident that he speaks of going to church very early in the morning, before going out to each ones' job.

Another, even earlier witness is from Egeria's early fourth-century Jerusalem pilgrimage account (24. 8-12):

But on the seventh day, the Lord's Day, there gather in the courtyard before cock-crow all the people, as many as can get in, as if it was Pascha. The courtyard is the "basilica" beside the Anastasis, that is to say, out of doors, and lamps have been hung there for them. Those who are afraid they may not arrive in time for cock-crow come early,and sit waiting there singing hymns and antiphons, and they have prayers between, since there are always presbyters and deacons there ready for the vigil, because so many people collect there, and it is not usual to open the holy places before cock-crow.

Soon the first cock crows, and at that the bishop enters, and goes into the cave in the Anastasis. The doors are all opened, and all the people come into the Anastasis, which is already ablaze with lamps. When they are inside, a psalm is said by one of the presbyters, with everyone responding, and it is followed by a prayer; then a psalm is said by one of the deacons, and another prayer; then a third psalm is said by one of the clergy, and a third prayer, and the Commemoration of All. After these three psalms and prayers they take censers into the cave of the Anastasis, so that the whole Anastasis basilica is filled with the smell. Then the bishop, standing inside the screen, takes the Gospel book and goes to the door, where he himself reads the account of the Lord's resurrection. At the beginning of the reading the whole assembly groans and laments at all that the Lord underwent for us, and the way they weep would move even the hardest heart to tears. When the Gospel is finished, the bishop comes out, and is taken with singing to the Cross, and they all go with him. They have one psalm there an a prayer, then he blesses the people, and that is the dismissal. As the bishop goes out, everyone comes to kiss his hand.

Then straight away the bishop retires to his house, and all the monazontes go back into the Anastasis to sing psalms and antiphons until daybreak. There are prayers between all these psalms and antiphons, and presbyters and deacons take their turn every day at the Anastasis to keep vigil with the people. Some lay men and women like to stay on there till daybreak, but others prefer to go home again to bed for some sleep.

From the above you can see that the first cock-crow is well before daybreak. Also, at the Anastasis we have to participation of the "spoudaioi", those monazontes referred to who were from the Sabas Lavra and were there in Jerusalem to serve the holy places, those who today are called the "phylakes tou taphou."

We can also clearly see the use of three antiphons, as is still retained in the use of the Typikon service for days without a feast, as well as the three antiphons prescribed for all great feasts. The number three, of course, is always in honor of the Holy Trinity.

Evident, also is the tradition of holding vigil on Saturday night, in honor of the resurrection, just as is still indicated in the sabaitic typika to this day. Additionally, this is why the mesonyktikon for Sunday morning, in the absence of a vigil, is in the order of the Studite/Constantinopolitan panychis (i.e., vigil).

Finally, we also see the practice of the reading of the Sunday heothinon Gospel from within the tomb by the Patriarch himself. This is why (i) we still read it today inside the bema, (ii) why, when a bishop is present, he should be present at its reading (hence, the reason why its reading is delayed till after the eighth ode of the orthros kanon) and (iii) why the reading of the orthros Gospel belongs to the clergy with the highest rank, as opposed to the Gospel of the Liturgy, which belongs to the deacons.

In any event, both examples clearly show how the early christians, even if they were not making vigil, came to church at first cock-crow. Anyone who has lived in the country knows that this is at the very first breaking of the darkness, say around 3-4AM.

Papouli,

The schedule of services throughout the year for the archdiocese of Athens are published in the dypticha each year; you can get an idea from there.

From St John Chrysostom's eighth baptismal catechesis:

16. I exhort you, therefore: let us seek the things which abide forever and never change. It was fitting, therefore, that I brought up this matter and that I exhorted all of you together, both those who have been initiated in the past and those who have just deserved the gift of baptism. On the days when we were continuously present at the tombs of the holy martyrs, we received an abundant blessing from those holy ones and enjoyed the rich benefit of their instruction. From now on, the continuity of our meetings will be broken off; hence, I must remind your loving assembly to keep ever ringing in your ears the memory of the important instruction those holy martyrs gave, and to hold spiritual things of greater importance than all the goods of this life.

17. And I urge you to show great zeal by gathering here in the church at dawn [orthron] to make your prayers and confessions to the God of all things, and to thank Him for the gifts He had already given. Beseech Him to deign to lend you from now on His powerful aid in guarding this treasure; strengthened with this aid, let each one leave the church to take up his daily tasks, one hastening to work with his hands, another hurrying to his military post, and still another to his post in the government. However, let each one approach his daily task with fear and anguish, and spend his working hours in the knowledge that at evening he should return here to the church, render an account to the Master of his whole day, and beg forgiveness for his falls. For even if we are on our guard ten thousand times a day, we cannot avoid making ourselves accountable for many and different faults. Either we say something at the wrong time, or we listen to idle talk, or we think indecent thoughts, or we fail to control our eyes, or we spend time in vain and idle things that have no connection with what we should be doing.

18. This is the reason why each evening we must beg pardon from the Master for all these faults. This is why we must flee to the loving-kindness of God and make our appeal to Him. Then we must spend the hours of the night soberly, and in this way meet the confessions of the dawn. If each of us manages his own life in this way, he will be able to cross the sea of this life without danger and to deserve the loving-kindness of the Master. And when the hour for gathering in church summons him, let him hold this gathering and all spiritual things in higher regard than anything else. In this way we shall manage the goods we have in our hands and keep them secure.

In the above we see St John's late fourth-century Constantinopolitan daily prayer programme for his flock. Notice, these are not monastics, but lay believers with all sorts of jobs. It is evident that he speaks of going to church very early in the morning, before going out to each ones' job.

Another, even earlier witness is from Egeria's early fourth-century Jerusalem pilgrimage account (24. 8-12):

But on the seventh day, the Lord's Day, there gather in the courtyard before cock-crow all the people, as many as can get in, as if it was Pascha. The courtyard is the "basilica" beside the Anastasis, that is to say, out of doors, and lamps have been hung there for them. Those who are afraid they may not arrive in time for cock-crow come early,and sit waiting there singing hymns and antiphons, and they have prayers between, since there are always presbyters and deacons there ready for the vigil, because so many people collect there, and it is not usual to open the holy places before cock-crow.

Soon the first cock crows, and at that the bishop enters, and goes into the cave in the Anastasis. The doors are all opened, and all the people come into the Anastasis, which is already ablaze with lamps. When they are inside, a psalm is said by one of the presbyters, with everyone responding, and it is followed by a prayer; then a psalm is said by one of the deacons, and another prayer; then a third psalm is said by one of the clergy, and a third prayer, and the Commemoration of All. After these three psalms and prayers they take censers into the cave of the Anastasis, so that the whole Anastasis basilica is filled with the smell. Then the bishop, standing inside the screen, takes the Gospel book and goes to the door, where he himself reads the account of the Lord's resurrection. At the beginning of the reading the whole assembly groans and laments at all that the Lord underwent for us, and the way they weep would move even the hardest heart to tears. When the Gospel is finished, the bishop comes out, and is taken with singing to the Cross, and they all go with him. They have one psalm there an a prayer, then he blesses the people, and that is the dismissal. As the bishop goes out, everyone comes to kiss his hand.

Then straight away the bishop retires to his house, and all the monazontes go back into the Anastasis to sing psalms and antiphons until daybreak. There are prayers between all these psalms and antiphons, and presbyters and deacons take their turn every day at the Anastasis to keep vigil with the people. Some lay men and women like to stay on there till daybreak, but others prefer to go home again to bed for some sleep.

From the above you can see that the first cock-crow is well before daybreak. Also, at the Anastasis we have to participation of the "spoudaioi", those monazontes referred to who were from the Sabas Lavra and were there in Jerusalem to serve the holy places, those who today are called the "phylakes tou taphou."

We can also clearly see the use of three antiphons, as is still retained in the use of the Typikon service for days without a feast, as well as the three antiphons prescribed for all great feasts. The number three, of course, is always in honor of the Holy Trinity.

Evident, also is the tradition of holding vigil on Saturday night, in honor of the resurrection, just as is still indicated in the sabaitic typika to this day. Additionally, this is why the mesonyktikon for Sunday morning, in the absence of a vigil, is in the order of the Studite/Constantinopolitan panychis (i.e., vigil).

Finally, we also see the practice of the reading of the Sunday heothinon Gospel from within the tomb by the Patriarch himself. This is why (i) we still read it today inside the bema, (ii) why, when a bishop is present, he should be present at its reading (hence, the reason why its reading is delayed till after the eighth ode of the orthros kanon) and (iii) why the reading of the orthros Gospel belongs to the clergy with the highest rank, as opposed to the Gospel of the Liturgy, which belongs to the deacons.

In any event, both examples clearly show how the early christians, even if they were not making vigil, came to church at first cock-crow. Anyone who has lived in the country knows that this is at the very first breaking of the darkness, say around 3-4AM.

Thursday, October 28, 2004

Levy and Velimirovic honorary doctorates

Two honorary doctorates were awarded by the National and Capodistrian University of Athens, Greece this past Monday, 18 October 2004.

The well-known professors, Milos Velimirovic and Kenneth Levy were the recipients.

Prof. Gregorios Stathis, a third generation Byzantine musicologist, also well known for his research in the field, professor of the Department of Music Studies introduced the recipients at the old university building just under the Acropolis in the Plaka area of historic Athens.

After the reading of the citations by the appropriate university professors and the presentation of the degrees and garbing, both professors offered papers:

M Velimirovic, "On the Byzantine influence in early slavonic chant"

K Levy, "Byzantine chant: some western perspectives"

The ceremony was concluded with the chanting of three hymns by the Maistores of the Psaltic Art, directed by Prof. A Chaldaiakis. After entering and chanting the megalynarion _Axion estin os alethos thn hypertheon_, the eighth and ninth odes of the kanon for Great and Holy Tuesday written by the monk Kosmas were chanted with the mele of Petros Lambadarios and Petros Byzantios in honor of K. Levy's work on certain Great Week troparia. The music programme was concluded with a verse of the Great Anoixantaria (Ps 103 [104]. 21b) according to the melos of the Byzantine composer Ioannes Kladas in honor of M. Velimirovic's work on the great vespers.

Present in the audience were a wealth of now fourth generation Byzantine musicologists, students of the University of Athens, as well as a number of well known researchers and choir directors, such as Michael Adamis, Kaite Romanou, Markos Dragoumis, Lykourgos Angelopoulos and others.

A truly memorable, but also historic meeting of three generations of Byzantine musicologists.

Congratulations to both recipients, sterling representatives of a second generations of Byzantine Musicologists and also members of the AMS!

The well-known professors, Milos Velimirovic and Kenneth Levy were the recipients.

Prof. Gregorios Stathis, a third generation Byzantine musicologist, also well known for his research in the field, professor of the Department of Music Studies introduced the recipients at the old university building just under the Acropolis in the Plaka area of historic Athens.

After the reading of the citations by the appropriate university professors and the presentation of the degrees and garbing, both professors offered papers:

M Velimirovic, "On the Byzantine influence in early slavonic chant"

K Levy, "Byzantine chant: some western perspectives"

The ceremony was concluded with the chanting of three hymns by the Maistores of the Psaltic Art, directed by Prof. A Chaldaiakis. After entering and chanting the megalynarion _Axion estin os alethos thn hypertheon_, the eighth and ninth odes of the kanon for Great and Holy Tuesday written by the monk Kosmas were chanted with the mele of Petros Lambadarios and Petros Byzantios in honor of K. Levy's work on certain Great Week troparia. The music programme was concluded with a verse of the Great Anoixantaria (Ps 103 [104]. 21b) according to the melos of the Byzantine composer Ioannes Kladas in honor of M. Velimirovic's work on the great vespers.

Present in the audience were a wealth of now fourth generation Byzantine musicologists, students of the University of Athens, as well as a number of well known researchers and choir directors, such as Michael Adamis, Kaite Romanou, Markos Dragoumis, Lykourgos Angelopoulos and others.

A truly memorable, but also historic meeting of three generations of Byzantine musicologists.

Congratulations to both recipients, sterling representatives of a second generations of Byzantine Musicologists and also members of the AMS!

Saturday, August 21, 2004

Adam's Family chant

I recall this particular point with fondness for the following reason. When I was teaching Byzantine Music 101 at Holy Cross in Brookline MA back in 1990-2 I had devised a kind of Mode Table for use by the beginning students as a help to learning the modes. It had space for the various modes in their respective genera (i.e. iv had three rows: heirmologic, sticheraric and papadic, etc.). One column would show the basis, another the dominant notes, another would recall a well know melos in that particular mode that could be easily recalled by these neophites; an example would be Phos hilaron for mode II or Christos aneste for mode I plagal, and so on. The last column, however, was blank for each student to fill in him or herself; in that last space they would enter any tune or song that helped then 'get into the mode'. The one that I got the biggest kick out of was when one student wrote in 'the Adam's family tune' for mode III: you know, where it goes "da da da dum; da da da dum; da da da dum [snap snap]"! I'll never forget it; it was his na na.

;-)

;-)

Monday, March 01, 2004

Liturgical, ahistorical fad

[In response to a letter circulated by an Orthodox bishop in the US.] It's too bad that people without a historical base try to use history without respect to the received tradition in order to support liturgical practices they personally would like to see applied, downgrading and ragging on flocks not under their pastorate.

First, I find the entire tone of the letter offensive. There is talk of 'the standard tradition which we have received from time immemorial' in reference to how 'our priests' celebrate the divine Liturgy in various parishes. It would be nice to know what 'standard tradition' the said respected writer has in mind; references don't hurt, in fact, a real reference to some monument of the Church's liturgical diataxis would go a long way in helping someone judge whether or not we're not really just dealing with _one_ writer's personal preferences in liturgical practice, but then that would be logical.

One point, no. 7, actually deals with practice and it is good to see that a distinction is made between concelebrated liturgies and liturgies served by a single priest. However, again, some actual reason or at least reference to sources would go a long way in dispelling the air of simple liturgical 'dictation'. _Why_ does a priest celebrating along not chant the entrance hymns, the phos hilaron, the apolytikia, kontakion, hagios ho theos, etc.? Is this where we are? Just tell us what we should do and 'we follow orders, sir!'? I think not.

Point 10 deals with the dialogue preceding the recitation of the Epistle reading in the divine Liturgy. Again, simple dictation is being applied here. If there is some 'standard tradition' regarding this dialogue it surely was not alluded by the writer. Do this; do this; do this and then do this. That's all it is. Not only that, but two prekeimenon verses are alluded to! What could they be? Any epistle I've ever opened have a prokeimenon with one verse before the epistle reading. Who knows? Maybe they've published another epistle book in that jurisdiction? If we're really talking about the received liturgical tradition of the Eastern Orthodox Church there is an established form of dialogue for the epistle reading from 'time immemorial'. Unfortunately, it's definitely not described in this document.

The real clincher, however, is point 19. Unfortunately, not only is the received liturgical tradition of the Eastern Orthodox Church ignored in this point, but even the canons of the church are set aside in favor of a 'policy of the Archdiocese [of the Greek Orthodox Church of America] from 1950! Not quite 'time immemorial', as suggested at the introduction. Most interesting is the use of the example of the kneeling service on Pentecost Sunday. The writer does not mention that the kneeling takes place _after_ the full dismissal of the divine Liturgy celebrating the great feast of holy Pentecost and even then only _after_ the entrance in the vespers of the next day, the Monday of the Holy Spirit, or first day after the feast of Pentecost.

Also not mentioned are the ancient canons of the church (which, by the way, have not been rescinded). Not only are we not talking about some local council canon, but we speak specifically of canon 20 of the first oecumenical council which states: '…it has seemed best to the holy Council for prayers to be offered to God while standing'. Hmm. My less than perfect reading of canon 90 of the sixth oecumenical council seems to find this issue clearly reinforced: 'We have received it canonically from our God-bearing Fathers not to bend the knee on Sundays when honoring the Resurrection of Christ, since this observation may not be clear to some of us, we are making it plain to the faithful, so that after the entrance of those in holy orders into the sacrificial altar on the evening of the Saturday in question, let none of them bend a knee until the evening of the following Sunday, when, after the entrance during the Lychnikon, again bending knees, we thus begin offering our prayers to the Lord…'. Sounds pretty clear to me. Here we even have mention of the specific point in the service after which we can again kneel: after the entrance in the vespers. Hmm. Interesting how our liturgical texts have preserved this very point in the vespers for the Holy Spirit. Imagine that?! The writer's comments betray a faulty reading of the most basic kind. I won't get into the fact that this very issue was the excuse used to 'rid' Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology of the famous 20th c Orthodox theologian, Fr G Florovsky; need I say more?

Maybe these canons aren't old enough, though? St Peter the Martyr of Alexandria who lived in the 3rd century also makes mention of the venerable ancient practice and true liturgical taxis 'from time immemorial' in his 15th canon saying, 'as for Sunday, on the other hand, we celebrate it as a joyous holiday because of His having risen from the dead, on which day we have not even received instruction to bend a knee'. A-hah: there's our 'time immemorial'.

So, according to this writer, if we choose to heed to the holy and god-bearing fathers of the oecumencal councils *and* ancient tradition as witnessed to from time even before the first oecumenical council we should be as those who see themselves as 'more orthodox than you are, people who see externals, outer trappings, as more essential than the fervent heart'. As if this is not enough, he also goes on to refer to what he calls 'a sad reality that the Orthodox people in Greece', who do not kneel at the epiklesis. He claims that they do not kneel because they 'do not find that special moment any different than the rest of the divine Liturgy'. Tell me. Where in any manuscript or printed edition of the eucholgion is the diataxis to kneel at the the time of the epiklesis offered?

Well, it doesn't stop there. Injury is followed by insult. The writer then goes on to condemn 'most Orthodox in Greece' for not receiving holy Communion, 'even monthly, and if they do, it is often after the divine Liturgy at the Deacon's doors, as sort of an afterthought'. Then he goes on to mock a priest serving the divine Liturgy in Greece who was 'simultaneously carrying on a conversation with another priest in the altar, while chanting the divine Liturgy'. This what why, 'of course, he did not kneel at the Epiklesis; it would have interrupted his conversation with the other priest'. How the one follows from the other I shall probably never know. I can, however, attest for the laxity of American piety with regards the preparation for the reception of the holy Mystery of Communion. Yes, dear writer, they do not feel comfortable in Greece approaching the holy Cup after spending the night out at a restaurant or movie theatre. Yes, most Orthodox in Greece will also not approach if they have not received a rule of communion from their spiritual father, either. I also do know how many times I was reprimanded while serving in the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America when I even mentioned the word confession. How often did I hear the retort, from clergy and lay alike, 'this isn't Greece! We don't do that here!' Or, another 'faithful' of the American church who told me, 'Father, we have a family tradition. We have breakfast together on Sunday mornings and then attend Church as a family'. What would our writer say if he knew the faithful here in Greece don't even eat antidoron if they've put anything in their mouth before coming to church?!

I remember attending a diocesan clergy meeting with an American bishop that has since fallen asleep in the Lord. He chose a church somewhat central to most clergy and scheduled a celebration of the divine Liturgy with his clergy and then meetings throughout the day. I was there early enough to get to the church before the bishop. When I did, the 'highly respected' proistamenos of the cathedral church was in pants and a shirt having a smoke just outside the altar. Inside was the holy proskomide he had prepared for the arrival of the bishop--paten and chalice with the gifts already cut, placed and poured. Of course, he had not taken kairo before starting the service of proskomide, neither was he vested, but I guess I shouldn't go by externals.

Somehow, I'm not convinced.

First, I find the entire tone of the letter offensive. There is talk of 'the standard tradition which we have received from time immemorial' in reference to how 'our priests' celebrate the divine Liturgy in various parishes. It would be nice to know what 'standard tradition' the said respected writer has in mind; references don't hurt, in fact, a real reference to some monument of the Church's liturgical diataxis would go a long way in helping someone judge whether or not we're not really just dealing with _one_ writer's personal preferences in liturgical practice, but then that would be logical.

One point, no. 7, actually deals with practice and it is good to see that a distinction is made between concelebrated liturgies and liturgies served by a single priest. However, again, some actual reason or at least reference to sources would go a long way in dispelling the air of simple liturgical 'dictation'. _Why_ does a priest celebrating along not chant the entrance hymns, the phos hilaron, the apolytikia, kontakion, hagios ho theos, etc.? Is this where we are? Just tell us what we should do and 'we follow orders, sir!'? I think not.

Point 10 deals with the dialogue preceding the recitation of the Epistle reading in the divine Liturgy. Again, simple dictation is being applied here. If there is some 'standard tradition' regarding this dialogue it surely was not alluded by the writer. Do this; do this; do this and then do this. That's all it is. Not only that, but two prekeimenon verses are alluded to! What could they be? Any epistle I've ever opened have a prokeimenon with one verse before the epistle reading. Who knows? Maybe they've published another epistle book in that jurisdiction? If we're really talking about the received liturgical tradition of the Eastern Orthodox Church there is an established form of dialogue for the epistle reading from 'time immemorial'. Unfortunately, it's definitely not described in this document.

The real clincher, however, is point 19. Unfortunately, not only is the received liturgical tradition of the Eastern Orthodox Church ignored in this point, but even the canons of the church are set aside in favor of a 'policy of the Archdiocese [of the Greek Orthodox Church of America] from 1950! Not quite 'time immemorial', as suggested at the introduction. Most interesting is the use of the example of the kneeling service on Pentecost Sunday. The writer does not mention that the kneeling takes place _after_ the full dismissal of the divine Liturgy celebrating the great feast of holy Pentecost and even then only _after_ the entrance in the vespers of the next day, the Monday of the Holy Spirit, or first day after the feast of Pentecost.

Also not mentioned are the ancient canons of the church (which, by the way, have not been rescinded). Not only are we not talking about some local council canon, but we speak specifically of canon 20 of the first oecumenical council which states: '…it has seemed best to the holy Council for prayers to be offered to God while standing'. Hmm. My less than perfect reading of canon 90 of the sixth oecumenical council seems to find this issue clearly reinforced: 'We have received it canonically from our God-bearing Fathers not to bend the knee on Sundays when honoring the Resurrection of Christ, since this observation may not be clear to some of us, we are making it plain to the faithful, so that after the entrance of those in holy orders into the sacrificial altar on the evening of the Saturday in question, let none of them bend a knee until the evening of the following Sunday, when, after the entrance during the Lychnikon, again bending knees, we thus begin offering our prayers to the Lord…'. Sounds pretty clear to me. Here we even have mention of the specific point in the service after which we can again kneel: after the entrance in the vespers. Hmm. Interesting how our liturgical texts have preserved this very point in the vespers for the Holy Spirit. Imagine that?! The writer's comments betray a faulty reading of the most basic kind. I won't get into the fact that this very issue was the excuse used to 'rid' Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology of the famous 20th c Orthodox theologian, Fr G Florovsky; need I say more?

Maybe these canons aren't old enough, though? St Peter the Martyr of Alexandria who lived in the 3rd century also makes mention of the venerable ancient practice and true liturgical taxis 'from time immemorial' in his 15th canon saying, 'as for Sunday, on the other hand, we celebrate it as a joyous holiday because of His having risen from the dead, on which day we have not even received instruction to bend a knee'. A-hah: there's our 'time immemorial'.

So, according to this writer, if we choose to heed to the holy and god-bearing fathers of the oecumencal councils *and* ancient tradition as witnessed to from time even before the first oecumenical council we should be as those who see themselves as 'more orthodox than you are, people who see externals, outer trappings, as more essential than the fervent heart'. As if this is not enough, he also goes on to refer to what he calls 'a sad reality that the Orthodox people in Greece', who do not kneel at the epiklesis. He claims that they do not kneel because they 'do not find that special moment any different than the rest of the divine Liturgy'. Tell me. Where in any manuscript or printed edition of the eucholgion is the diataxis to kneel at the the time of the epiklesis offered?

Well, it doesn't stop there. Injury is followed by insult. The writer then goes on to condemn 'most Orthodox in Greece' for not receiving holy Communion, 'even monthly, and if they do, it is often after the divine Liturgy at the Deacon's doors, as sort of an afterthought'. Then he goes on to mock a priest serving the divine Liturgy in Greece who was 'simultaneously carrying on a conversation with another priest in the altar, while chanting the divine Liturgy'. This what why, 'of course, he did not kneel at the Epiklesis; it would have interrupted his conversation with the other priest'. How the one follows from the other I shall probably never know. I can, however, attest for the laxity of American piety with regards the preparation for the reception of the holy Mystery of Communion. Yes, dear writer, they do not feel comfortable in Greece approaching the holy Cup after spending the night out at a restaurant or movie theatre. Yes, most Orthodox in Greece will also not approach if they have not received a rule of communion from their spiritual father, either. I also do know how many times I was reprimanded while serving in the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America when I even mentioned the word confession. How often did I hear the retort, from clergy and lay alike, 'this isn't Greece! We don't do that here!' Or, another 'faithful' of the American church who told me, 'Father, we have a family tradition. We have breakfast together on Sunday mornings and then attend Church as a family'. What would our writer say if he knew the faithful here in Greece don't even eat antidoron if they've put anything in their mouth before coming to church?!

I remember attending a diocesan clergy meeting with an American bishop that has since fallen asleep in the Lord. He chose a church somewhat central to most clergy and scheduled a celebration of the divine Liturgy with his clergy and then meetings throughout the day. I was there early enough to get to the church before the bishop. When I did, the 'highly respected' proistamenos of the cathedral church was in pants and a shirt having a smoke just outside the altar. Inside was the holy proskomide he had prepared for the arrival of the bishop--paten and chalice with the gifts already cut, placed and poured. Of course, he had not taken kairo before starting the service of proskomide, neither was he vested, but I guess I shouldn't go by externals.

Somehow, I'm not convinced.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)