What we say, hear and sing in worship shapes our faith. In the case of words, rhythm and rhyme create poetry, clothing the words so they might penetrate deeper into the mind and soul, giving strength to the logos hidden behind the words. In the case of poems, melos (melody) blends with the logos so as to bring us more easily before the Lord, in turn, affecting our whole being through the direct, intimate one-on-one contact with God and persuading us to good works. In short, as St John Chrysostom would write in the fourth century, the poetry (logos) and melody (melos) make the process of prayer and the catechetical word less a chore.

“When God saw that many men were rather indolent, that they came unwillingly to Scriptural readings and did not endure the labor this involves, wishing to make the labor more grateful and to take away the sensation of it, He blended melody with prophecy in order that, delighted by the modulation of the chant, all might with great eagerness give forth sacred hymns to Him. For nothing so uplifts the mind, giving it wings and freeing it from the earth, releasing it from the chains of the body, affecting it with love of wisdom, and causing it to scorn all things pertaining to this life, as modulated melody and the divine chant composed of number” (PG LV, 155-159, from St John Chrysostom’s homily on Psalm XLI).

The strength of the metered word and modulated melody appear at both the most joyous and most difficult, even tragic, points of human existence. When the people of Israel crossed the Red Sea, “then sang Moses and the children of Israel this song unto the Lord, and spake, saying, I will sing unto the Lord, for he hath triumphed gloriously…” (Ex. 15. 1). On the other end of the spectrum of human existence, in the late 1940s, shortly before his death in a Siberian prison camp, a Russian Archpriest by the name of Gregory Petrov composed his own song to the Lord, an Akathist of Thanksgiving, in which, amidst all his personal suffering, his spirit welling up with gratitude, confessed:

“Immortal King of the ages,

Holding within your right hand

all the paths of human life

Through the power of your saving providence,

We thank you for all your acts of goodness,

Manifest and hidden, for the life on earth,

And the heavenly joys

of your kingdom to come.

Extend your mercy also into the future

for us who sing:

Refrain. Glory to you, O God, unto the ages.”

So it is clear that at the point of origin of any divine hymn or sacred musical composition is the relationship of prayer, a dialogue with God, either man reaching out to God or God touching man. The hymn or music is either the believer’s vocal response to contact with the divine or the believer’s attempt to reach out to the divine in thanksgiving, doxology or supplication. Apart from being a means of worship, it is also clear that the root of the rhythm (poetry) and sound (melody) of sacred music is also an inspired expression of faith. A confession of what one believes about God, the Saints, neighbor and the world he or she lives in. As such an expression it is worthy of examination. In time, over the centuries, changes in hymn forms will be related to changes in liturgical development and liturgical worship (practice), evolving especially during times of dynamic social change in the life of the Church, times where the theology (thought)—the perception of how one’s faith is to be lived—is challenged, be it from within or without. Theological and sociological developments interact, leaving some mark on liturgy, whether it be the hymns or their music. This form of looking at liturgical music from the vantage point of its place in the history of liturgy and an expression of social change is a widening of the fields of musicology and theology.

Thursday, December 30, 2004

Tuesday, December 28, 2004

Nativity Vigil

This year I celebrated the feast of our Lord's Nativity with a vigil at a women's monastery on Hymitos mountain, must be Koropi. The monastery's katholikon is dedicated to the Nativity and is known as "Bethlehem." We started at about 10:30PM and finished around 6:30AM. I was on the road back to Piraeus by 7AM and caught the 8AM boat back to Aegina.

There's always alot of talk about how "beautiful" Christmas is in the West (i.e. US, UK, Germany, etc.), but I think there's no match to the spiritual stregnth that should and could be.

In recent years, apparently influenced by powers not known to me, there is a push to begin services later and later. The idea is that people can't wake up early for Church. When I came to Greece for studies the first time, back in 1988, I remember entering a Church on Christmas morning at 5:15AM and not finding a seat! The announced time for the start of the service was 5AM. If you check the old "Farlekas," you see that ten, twenty and thirty years ago the services began even earlier—3:15AM, 4AM. We would call this a "Sunrise" service in American Protestant circles. It's basically an abbreviated vigil service for the parishes.

The monastic diataxis begins with the Great Apodeipnon up to the doxology and then finishes the vespers that was not completed in the morning by going directly into the Lity, Aposticha, Blessing of the loaves and then continues as would any other vigil, with the reading, hexapsalmos and the rest of the orthros followed by the hours, metalipsis, typika and divine Liturgy.

The parish diataxis (Konstantinos/Biolakes typika) begins with a kind of mesonyktikon, followed by the orthros and divine Liturgy.

In America most Orthodox Churches are mostly empty on Christmas morning. The parishes with more than one priest, with the blessings of the bishops, have moved the services to early afternoon. This means all the larger cathedrals. People wanna come to Church early in the evening, take communion and then go home, open presents and feast. Christmas morning becomes a sleep-in day.

How is this a "beautiful" Christmas?

Christmas is not lights, decorated trees, presents and richly laden tables…

"O Lord my God, I know that I am not worthy, nor sufficient, that Thou shouldest come under the roof of the house of my soul, for all is desolate and fallen, and Thou hast not in me a place worthy to lay Thy head. But even as from on high Thou didst humble Thyself for our sake, so now conform Thyself to my lowliness. And even as Thou didst deign to lie in a cave and in a manger of irrational beasts, so also deign to lie in the manger of mine irrational soul and to enter my defiled body."

This is the attitude the Church fathers brought to Christmas prayer.

Somehow, it seems to me that the situation in America is more than assimilation. Something else is operative. Something un-American. To what extent do allow a weak, Anglo-Protestant worship life to infiltrate into our rich Orthodox Christian heritage? God forbid anyone take the tyropittes, spanakopittes, pastitsia and feta cheese off our Christmas dinner menu. Then we'd get upset!

Have we maybe taken something much more worthy off our "table"?

There's always alot of talk about how "beautiful" Christmas is in the West (i.e. US, UK, Germany, etc.), but I think there's no match to the spiritual stregnth that should and could be.

In recent years, apparently influenced by powers not known to me, there is a push to begin services later and later. The idea is that people can't wake up early for Church. When I came to Greece for studies the first time, back in 1988, I remember entering a Church on Christmas morning at 5:15AM and not finding a seat! The announced time for the start of the service was 5AM. If you check the old "Farlekas," you see that ten, twenty and thirty years ago the services began even earlier—3:15AM, 4AM. We would call this a "Sunrise" service in American Protestant circles. It's basically an abbreviated vigil service for the parishes.

The monastic diataxis begins with the Great Apodeipnon up to the doxology and then finishes the vespers that was not completed in the morning by going directly into the Lity, Aposticha, Blessing of the loaves and then continues as would any other vigil, with the reading, hexapsalmos and the rest of the orthros followed by the hours, metalipsis, typika and divine Liturgy.

The parish diataxis (Konstantinos/Biolakes typika) begins with a kind of mesonyktikon, followed by the orthros and divine Liturgy.

In America most Orthodox Churches are mostly empty on Christmas morning. The parishes with more than one priest, with the blessings of the bishops, have moved the services to early afternoon. This means all the larger cathedrals. People wanna come to Church early in the evening, take communion and then go home, open presents and feast. Christmas morning becomes a sleep-in day.

How is this a "beautiful" Christmas?

Christmas is not lights, decorated trees, presents and richly laden tables…

"O Lord my God, I know that I am not worthy, nor sufficient, that Thou shouldest come under the roof of the house of my soul, for all is desolate and fallen, and Thou hast not in me a place worthy to lay Thy head. But even as from on high Thou didst humble Thyself for our sake, so now conform Thyself to my lowliness. And even as Thou didst deign to lie in a cave and in a manger of irrational beasts, so also deign to lie in the manger of mine irrational soul and to enter my defiled body."

This is the attitude the Church fathers brought to Christmas prayer.

Somehow, it seems to me that the situation in America is more than assimilation. Something else is operative. Something un-American. To what extent do allow a weak, Anglo-Protestant worship life to infiltrate into our rich Orthodox Christian heritage? God forbid anyone take the tyropittes, spanakopittes, pastitsia and feta cheese off our Christmas dinner menu. Then we'd get upset!

Have we maybe taken something much more worthy off our "table"?

Saturday, December 25, 2004

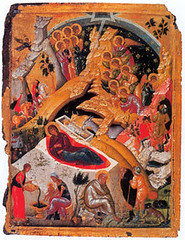

15th c Nativity icon; Athens: Byzantine Museum

Oikos.

Bethlehem opened Eden, come let us behold;

We have found joy in this hidden place,

comelet us seize

The pleasures of paradise within the cave;

There appeared an unwatered root

which sprouted forgiveness;

There was found an undug well

From which David once yearned to drink;

And there the Virgin brought forth an infant

Who at once quenched their thirst,

that of Adam and of David.

Come, then, let us hasten to this place

where there has been born

A newborn babwe, the pre-eternal God.

St Romasnos Melodos

Prayers for a blessed Christmas and New Year full of His grace!

Bethlehem opened Eden, come let us behold;

We have found joy in this hidden place,

comelet us seize

The pleasures of paradise within the cave;

There appeared an unwatered root

which sprouted forgiveness;

There was found an undug well

From which David once yearned to drink;

And there the Virgin brought forth an infant

Who at once quenched their thirst,

that of Adam and of David.

Come, then, let us hasten to this place

where there has been born

A newborn babwe, the pre-eternal God.

St Romasnos Melodos

Prayers for a blessed Christmas and New Year full of His grace!

Tuesday, December 21, 2004

Tradition and Change: American Assimilation vs Acculturation

It's really everywhere if you stop and think, even the Iraqi war. Age-old traditions with a history, cultural life and outlook all their own coming face to face with modernity in the post-modern world. When either side seems threatened, tradition or change, the meeting point can contain a degree of tension. It is a challenge to both sides.

Relating to the sacred sound, the traditional psaltic art of the Orthodox Christian Church, especially Hellenic in origin, but subsequently affecting the other linguistic Orthodox traditions, it is no secret that this age-old sacred chant form, more commonly known as Byzantine Chant, has been challenged in the context of North American Orthodox Christianity. And I think it's fair to say, not just the chant, but that would get us onto other topics.

The basic question is how to acculturate this aspect of Orthodox Christian practice without assimilation into modern, secularized American "entertainment" worship. There's much to explain and much to explore, but there is also much to be gained.

What was most surprising to me, when I was finally face to face with the reality, is the fact that the challenge was not unique to the American cultural scene. The sacred music problem in the North American Orthodox Christian jurisdictions coming out of this liturgical chant tradition is actually a carry-over from the old country. It's the same challenge modernity gave to sacred Orthodox Iconography, another age-old liturgical art form, and even monasticism. The difference is that while both traditional liturgical art forms—iconography and chant—eventually prevailed in Greece and other traditionally Orthodox homelands, the same has not occured in North America for the chant.

Amidst the backdrop of all the talk on Orthodox leadership, clergy-laity relations, autocephaly, archdiocesesan and parish by-laws, parish councils, uniform codes and the rest, the tiny corner of our traditional liturgical chant will, no doubt, be viewed as quite an esoteric exercise by many, maybe even most.

Relating to the sacred sound, the traditional psaltic art of the Orthodox Christian Church, especially Hellenic in origin, but subsequently affecting the other linguistic Orthodox traditions, it is no secret that this age-old sacred chant form, more commonly known as Byzantine Chant, has been challenged in the context of North American Orthodox Christianity. And I think it's fair to say, not just the chant, but that would get us onto other topics.

The basic question is how to acculturate this aspect of Orthodox Christian practice without assimilation into modern, secularized American "entertainment" worship. There's much to explain and much to explore, but there is also much to be gained.

What was most surprising to me, when I was finally face to face with the reality, is the fact that the challenge was not unique to the American cultural scene. The sacred music problem in the North American Orthodox Christian jurisdictions coming out of this liturgical chant tradition is actually a carry-over from the old country. It's the same challenge modernity gave to sacred Orthodox Iconography, another age-old liturgical art form, and even monasticism. The difference is that while both traditional liturgical art forms—iconography and chant—eventually prevailed in Greece and other traditionally Orthodox homelands, the same has not occured in North America for the chant.

Amidst the backdrop of all the talk on Orthodox leadership, clergy-laity relations, autocephaly, archdiocesesan and parish by-laws, parish councils, uniform codes and the rest, the tiny corner of our traditional liturgical chant will, no doubt, be viewed as quite an esoteric exercise by many, maybe even most.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)